The Project

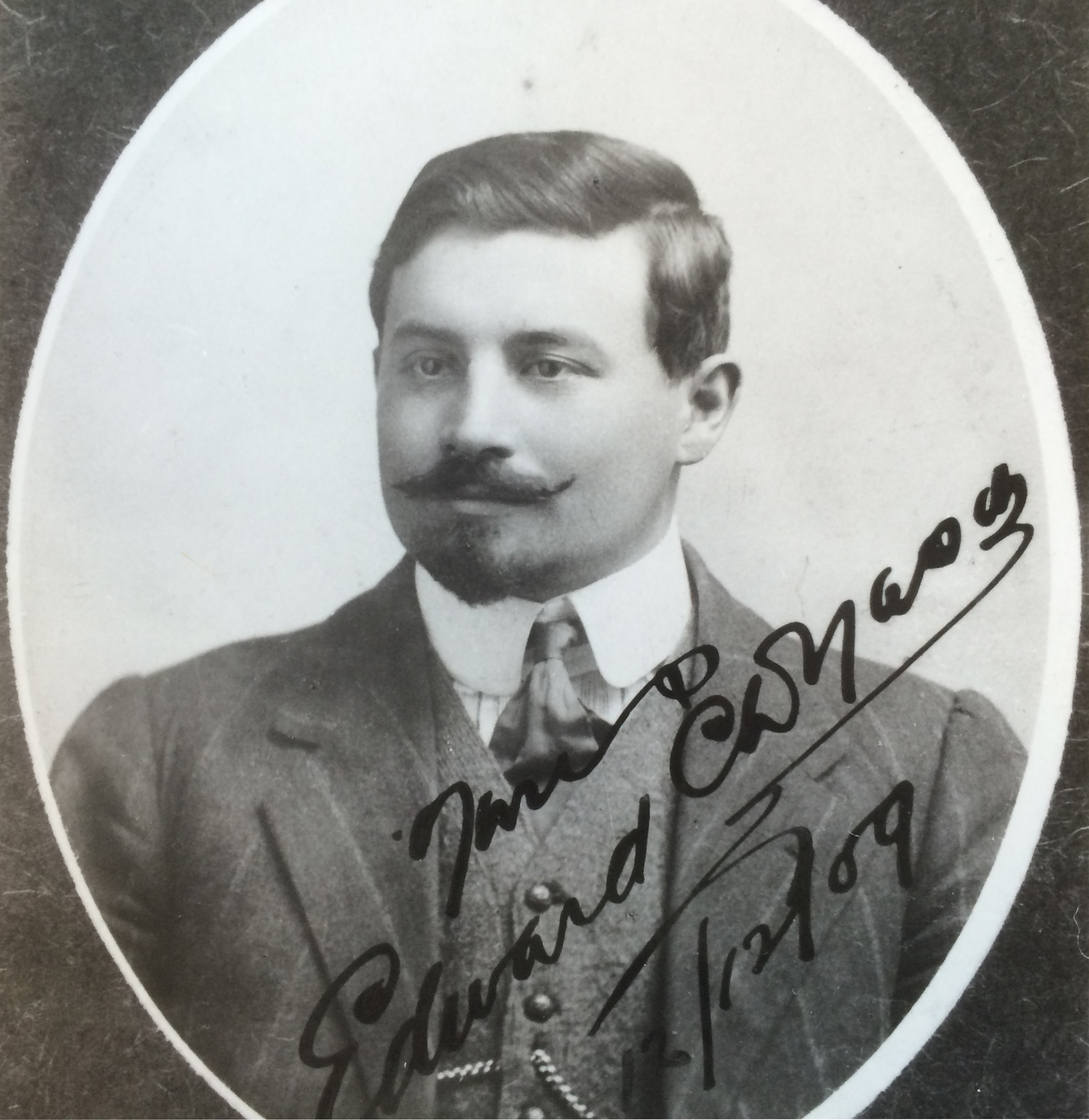

This project will produce a biography of Edward Dyason based upon a substantial archive of diaries and correspondence. The aim is not to explain why he chose one or another set of ideas or actions but to bring his voice into the narrative, to let him, as far as possible, speak for himself. The result will be a personal and a social history that will not only illuminate the life of an unusual person but also the world in which he lived.

The sweetness of an ever-enlarging horizon

The foundations of Dyason’s rationalism and his belief in science as the driver of progress, were laid during his university years, studying for degrees in science and mining engineering. He adopted a philosophical perspective that enabled him to navigate the difficulties he faced at this time, arising mostly from his sexual adventuring. Along the way he learned slowly to extract the good from the bad in his experiences. He thought of himself as a philosopher and, after some backsliding, later developed his perspective further through reading.

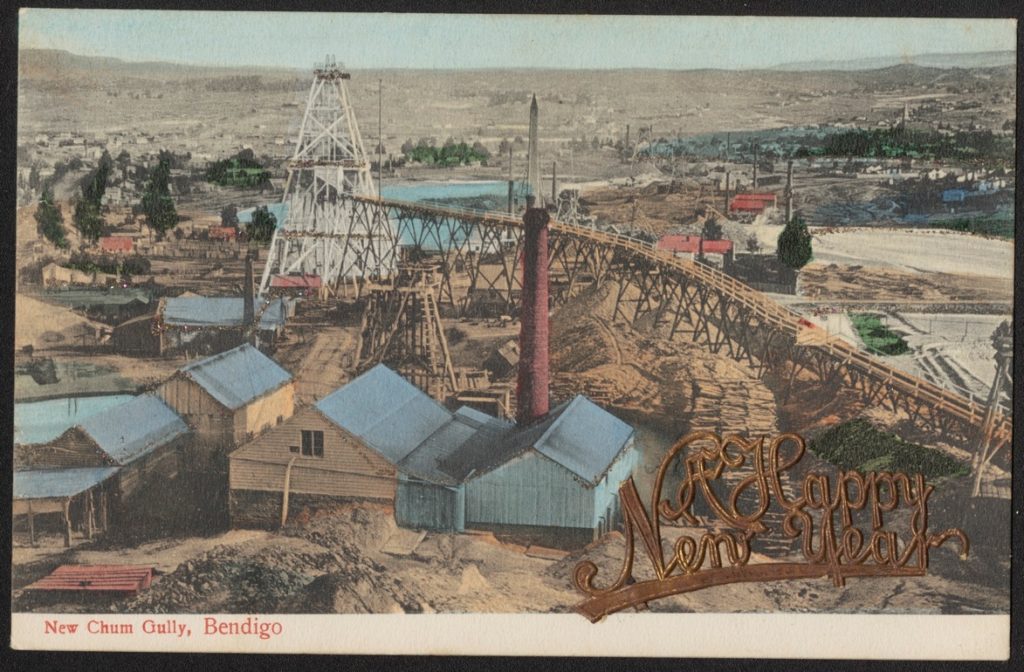

Bendigo and the gold mining industry

Dyason was born in Bendigo and strongly influenced by the approach taken by the city’s large mining investors, including his father, Isaac. These men, most of them part of the gold rush generation, had great faith in Bendigo’s gold resources. They took a long-term view of their speculations and while they enriched themselves they also used their gains to develop the industry and the local community. In the same spirit Dyason initiated two attempts to halt the decline in mining at Bendigo. His first attempt was made at the end of World War I when it seemed that wartime conditions would stifle not only Bendigo, but the national gold mining industry. He was the prime mover in the formation of the Gold Producers Association in 1919. His second attempt to revive Bendigo’s mines was in the early 1930s when development appeared economic because of a rise in the price of gold. Neither attempt was successful because of circumstances beyond local control.

Edward Dyason & Co

Dyason was the principal of Edward Dyason & Co. The firm offered a range of financial services including stockbroking, underwriting, company development and foreign exchange broking. The funds necessary for such operations were secured through connections Dyason established with firms in London and New York. The best estimate of the nature and extent of Dyason’s activities is found in the comment made by Sir Ian Potter, a prominent financial figure in post-World War II Australia. He came to work with Dyason after completing his economics degree at the University of Sydney in the late 1920s. He later recalled that working with Dyason gave him the breakthrough in his career he was looking for and the kind of experience that was available nowhere else in Sydney or Melbourne apart from J.B. Were & Son.

A pioneer in the development of economic study in Australia

These words appeared in a tribute to Dyason after his death by Professor Douglas Copland, founding dean of the Department of Commerce at the University of Melbourne. He went on to state that Dyason’s enthusiasm, practical guidance and financial support contributed greatly to the advances made in the discipline in the 1920s.

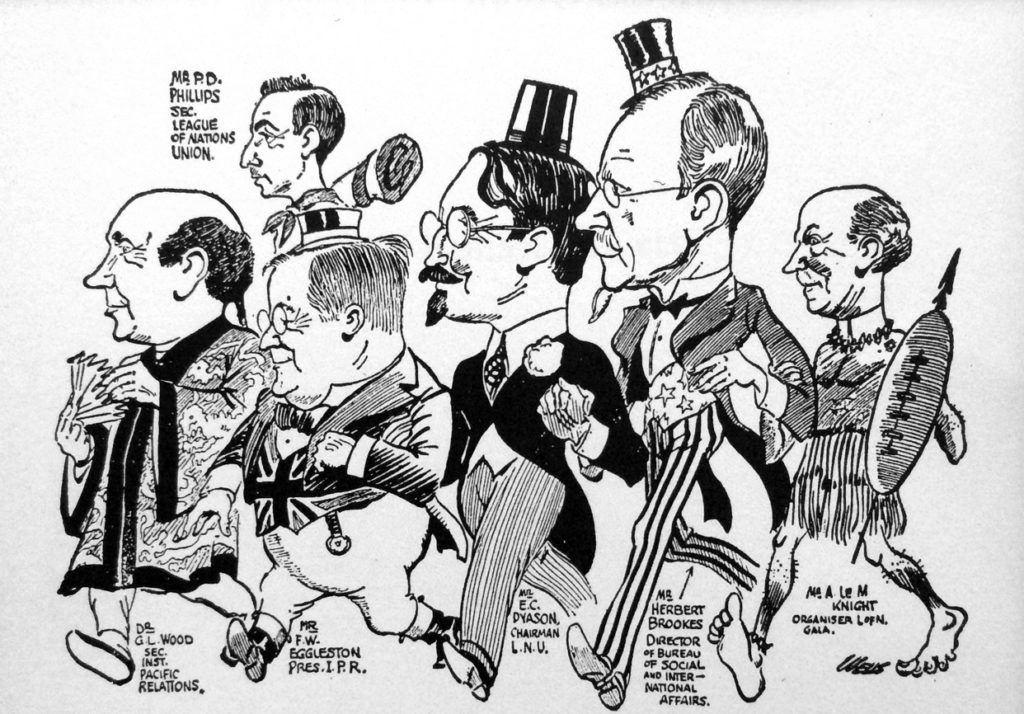

A driving force in the establishment of the Australian Institute of International Affairs

Dyason’s internationalism led him into an association with like-minded people after World War I, to provide and disseminate material to foster a greater understanding in the general population and in government, of the nation’s relations with Asia and the new British Commonwealth of Nations. The outcome of this movement to secure respectability for an Australian foreign policy was the formation of the Australian Institute of International Relations (AIIA). The Austral Asiatic Bulletin, instigated by Dyason, was a forerunner to the Institute’s journal, Australian Outlook.Dyason was not only a driving force, his managerial skills and financial contribution were vital to the survival of the AIIA during World War II.

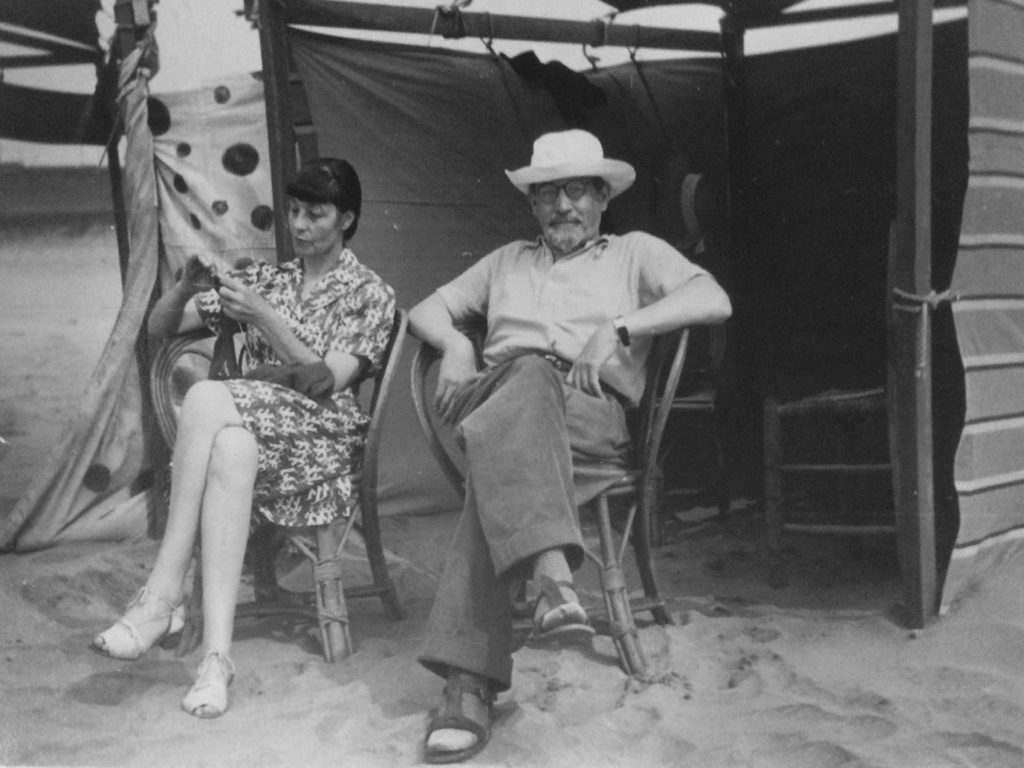

Wandiligong

Dyason came to north-east Victoria around 1912 to inspect gold mines. He took a liking to the area and bought land with a creek running through and a small cottage. His agricultural activities began with the cultivation of walnuts. He later moved into cattle in partnership with a local man, Fred Mommsen. The cottage was a base for restorative holidays for Dyason, his family and friends and for exploring the mountains on foot, on horseback and skis. It was the starting point, in July, 1929, during the best snowfall for years, for an exploratory trip led by Fred Mommsen, which took Dyason and a few other skiers, from Harrietville to Mount Hotham and across the plains to Mount Cope hut.

Melbourne’s Modern Art Movement

Dyason was interested in modernist painting and supported Sam Atyeo, a rising but impoverished talent in the early 1930s. In addition to financial support Dyason employed Atyeo to design a new façade for the building in Flinders’ Lane that came to be known as Regency House and later, to design the house he built at Narbethong. He also took an interest in Neil Douglas, a young painter gardener and environmentalist. Douglas helped with creating a garden of native plants at Narbethong.

Disappointment and Revival

When the Australian economy fell into depression in 1930, government and business saw deflation as the only rational response. Dyason was greatly concerned about the inequity of this approach to the problem and the social unrest it would generate. He advocated strenuously for measures that included an inflationary element aimed at stimulating opportunities for employment, a response similar to that later described as ‘Keynesian’. He failed to attract substantial support from either the left or the right of politics. With his faith in science shaken and semi-retired from business because of ill-health, he looked for a solution in a philosophical project aimed at bridging the gap between the natural and the social sciences. For personal reasons, he went to America in 1940, later choosing to see out the war in Buenos Aries and then moving to London. He died suddenly in October, 1949, crossing the Atlantic from New York to London on the Queen Mary, after representing the Australian Institute of International Relations at a Commonwealth conference in Canada.